The artistry of the Malay world has always captured the imagination of Dr Muhammad Pauzi Abdul Latif, an avid collector of its artefacts, writes Ninot Aziz.

ABOUT 100 years ago, one could travel by sampan from Kampung Bukit Kuda in Klang right up to Sungai Gombak and all the way to Masjid Jamek.

We can only imagine what the view from such a trip would have been like. Virgin jungle. Sounds of the wild. Rivers so crystal-clear that you could probably see tiger prawns and little fishes dancing in the water.

An avid collector of Malay world artifacts and “rescuer” of traditional Malay houses, Dr Muhammad Pauzi Abd Latif remembers his grandfather Pak Samad Majid regaling him with tales of such waterways and how the sampan could take you to the city in days long gone by. Supplies and goods were transported to Kuala Lumpur from Klang via this route.

A sampan maker, Pak Samad moved from Temerloh, Pahang to Kampung Kuda in the 1940s to practise his trade by the Klang River.

His daughter Zainab and then-grandson Muhammad Pauzi, or Poji as he was fondly called, were both born in Kampung Bukit Kuda. Poji used to spend hours watching his grandfather build his boats.

The boy was eventually allowed to help with minor woodwork and carpentry. Poji learnt to check for leaks by filling up new boats with water and to check the alignment of the boats by immersing them in the river.

Pausing for a moment to recall his childhood, Pauzi, the director of Universiti Putra Malaysia’s (UPM) Malay Heritage Museum, shares that sailing out to sea with his grandfather on a new sampan to test its worthiness number among the best memories he has of his childhood.

CALL OF HISTORY

In school, history was Pauzi’s favourite subject even as he aspired to be a lawyer. Yet his passion for the written word led him finally to the world of communications.

However, the love for history remained. Smiling, he confides that he always yearned to see, touch and collect items that connect us to our history.

He also enjoyed travelling locally, to little towns and villages like Besut and Pasir Mas. Very quickly the East Coast became his favourite local destination and it was there that he met with woodwork adiguru (master) Norhaiza Noordin. This made him appreciate the beauty and heritage of wood carving even more.

Soon, it dawned on the professor that the artistry of the Malay World was not limited to wood-carving, but also in metal works, textiles and manuscripts.

His collection quickly grew bigger and he found himself travelling far and wide to obtain wood carvings, textiles, traditional weapons, manuscripts and ceramics artifacts. He scoured known collectors’ havens such as Patani, Indonesia, the UK and the Netherlands.

One of his prized pieces is a Malay matchlock gun or the Istinggar. The Istinggar was used as early as the 1500s and, according to the Malay Annals, was used against the Portuguese in the 1511 invasion in Malacca.

In the story of Hikayat Megat Terawis, for instance, the hero Megat Terawis defeated his opponent Tok Saban using a specially-made bullet fired through an Istinggar.

Pauzi, through his friend Arjan Hollestelle in Portugaal, Netherlands, acquired an Istinggar in prime condition in 2015.

The Malays, explains Pauzi, specialised in metal works like pewter and brass and silver and gold. Silver pieces are not only exquisite and functional. They also have a longstanding history in Kelantan.

Silver boxes, jewellery and dining-ware are of the highest quality and have been used in royal households for ceremonies since ancient times. Sadly, the famed silversmiths are disappearing.

Pauzi’s friend, Pak Daud of Kota Baru who taught him about silverware, is perhaps among the last silversmiths in the country.

In 2016, UPM published a book co-written by Pauzi together with Professor Abdul Muati Ahmad titled Keris Warisan Melayu.

The art of keris-making, says Pauzi, is a culmination of the knowledge in metalwork. A good keris is made of, in some instances, up to 22 types of metal. Really superior keris should be able to “stand” on its dagger point or on its holder, being balanced and symmetrical in its design.

It’s a marvel of sorts that lead many who view this phenomenon for the first time to attribute it to magic.

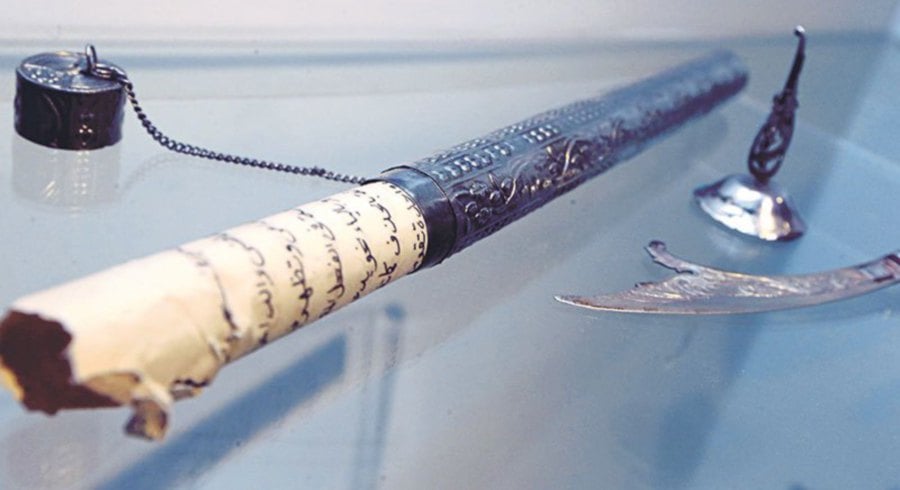

But Malay manuscripts continue to be Pauzi’s favourite collection as he considers them to be the pinnacle of Malay art and thought leadership.

His history teacher, none other than the renowned Professor Dr Harun Mat Piah, once told him; “If you want to see the intellectual thought of the Malay people and their wisdom, read the Malay manuscripts. Then you will know how knowledgeable they are.”

By reading these manuscripts, we can understand the intellectual thinking of our ancestors from days past, believes Pauzi.

He continues by saying that the wide variety of topics in Malay manuscripts is proof and testimony that our ancestors were rich in knowledge, smart, and were great inventors.

At UPM’s Malay Heritage Museum which houses many of Pauzi’s collection, there’s a display of manuscripts that focus on skills and knowledge — on metallurgy, star charting, literature, spiritual, religious — and even one on the rules of football!

TIMELESS

Taking a bite of goreng pisang at his favourite spot at Warung Selera Kampung in the compounds of the university, Pauzi appears to be lost in thought.

A long pause ensues before he eventually offers: “Malay craftsmanship, beauty and function come together to produce an artifact that is timeless and enduring. Unfortunately, the skills and craftsmanship needed to produce these works of art are fast disappearing. It’s no longer viable or sustainable for a craftsman or adiguru (master) as the demand is niche and select.”

His tone sombre, he concludes: “The younger generation today doesn’t seem to recognise the value of these heirlooms and therefore they are slowly fading away.”

Just like the rivers that used to connect Pauzi’s hometown to Kuala Lumpur and the sampans that used to be such an important mode of transportation in our not too distant past, our heritage too will fade away like the forgotten waterways of the forest. Never to be recovered.